Alice and the magic mirror

‘Taking time to reflect, mindfully, can turn experience into wisdom.’ A story for life’s Wisdom Years by Margaret Silf.

DLT Writing for You: an Intelligent, Inspirational, Inclusive newsletter from Darton, Longman and Todd

Contents

Alice and the magic mirror

Margaret Silf

‘Taking time to reflect, mindfully, can turn experience into wisdom.’ A story for life’s Wisdom Years by Margaret Silf.

It was a miserable morning, grey and drizzly – ‘dreich’ as they call it in Scotland. It was May, but it felt like November and the weather forecast predicted an unrelenting advance of low pressure zones. Sometimes Alice felt as though her life was itself becoming a low pressure zone – not much going on now that she was retired and apparently invisible to the busy wider world, put out to grass in a quiet corner where she wouldn’t cause any bother.

Not the best start to the day, she mused, as she put down her hairbrush and took a last rueful look in the mirror. The face that stared back was weary and dejected and looked every year of its age. She buried her head in her hands and let the mood wash over her. Family and friends were kind and loving but scattered far and wide. It was hard to stay connected with them in a real, rather than a virtual way. Some had already died and others were facing declining health. She imagined herself standing on a gravelly beach as the tide went out, taking her zest for life with it.

But this was no way to live. She took a deep breath, shook herself free of the mounting gloom and readied herself to launch into the new day. It happened that at that very instant a stray, but determined sunbeam broke through the heavy cloud cover. Startled by the unexpected moment Alice glanced again into her mirror in this new light and found herself contemplating a different version of herself.

Perhaps a single ray of light is all it takes to break the grip of the darkness. Whatever the reason, the Alice who was returning her gaze had a brightness about her. Her face was still lined and wrinkled but the wrinkles looked more like an intriguing map revealing the pathways of experience through the landscape of her life. Her hair, once described by her friends as ‘rich mouse’, was still grey, but now the many strands of silver were gleaming in the stream of morning light. Her sleep-dulled eyes were shining, her just-awakening brain eager for another day’s adventure. What had changed?

Reflecting. That must be it. Wasn’t that what mirrors were all about? It felt almost as though her mirror held magical powers. She had looked into it with regrets – for the many things she would never do again, the many places she would never visit again. And the mirror was reflecting them back as gratitude – that she had ever had all those experiences at all. There was heartache for her losses – of health, mobility, status and independence, and the fear of more to come. The mirror reflected this back in the shape of gifts – winter gifts that had needed a lifetime to ripen, as experience gradually transformed into wisdom, and short-term thinking expanded into a longer perspective on life and a deeper understanding of what really matters. With the tyranny of phones, schedules and deadlines now consigned to history, she could focus more on being than doing, so the mirror was suggesting. She wondered whether perhaps her life, her true self, was in fact not diminishing but ripening, and this new awareness gave her a different sense of her own value.

Ripening. The mirror seemed to echo the word back to her. What she had seen as dead leaves falling into inevitable disintegration now looked more like the ripe fruits of a mature tree bringing much-needed nourishment to a hungry world. A cycle of life where November would yield to another May, where yesterday’s life, well lived, would be her legacy to tomorrow’s world and where ‘nothing left to lose’ could also be seen as ‘everything still to give’. Perhaps, the mirror was proposing, this last chapter of her life was the most important of all, the chapter that would make sense of all the narrative that had gone before. Perhaps these struggling, fading years were, in reality, full of meaning. Perhaps they were her Wisdom Years.

* * *

As the years advance we are likely to have many moments when, like Alice, we feel irrelevant and wonder what our lives have amounted to, as so much of what we once thought was important slips through our fingers like sand on the seashore. There isn’t a magic mirror. Of course there isn’t. The magic lies in the word ‘reflecting’. Taking time to reflect, mindfully, on our experience turns that experience into wisdom, and wisdom is the great gift we have to bring to the world – a gift that takes time to grow and ripen. This process lies at the heart of what we might even regard as the vocation of our later years.

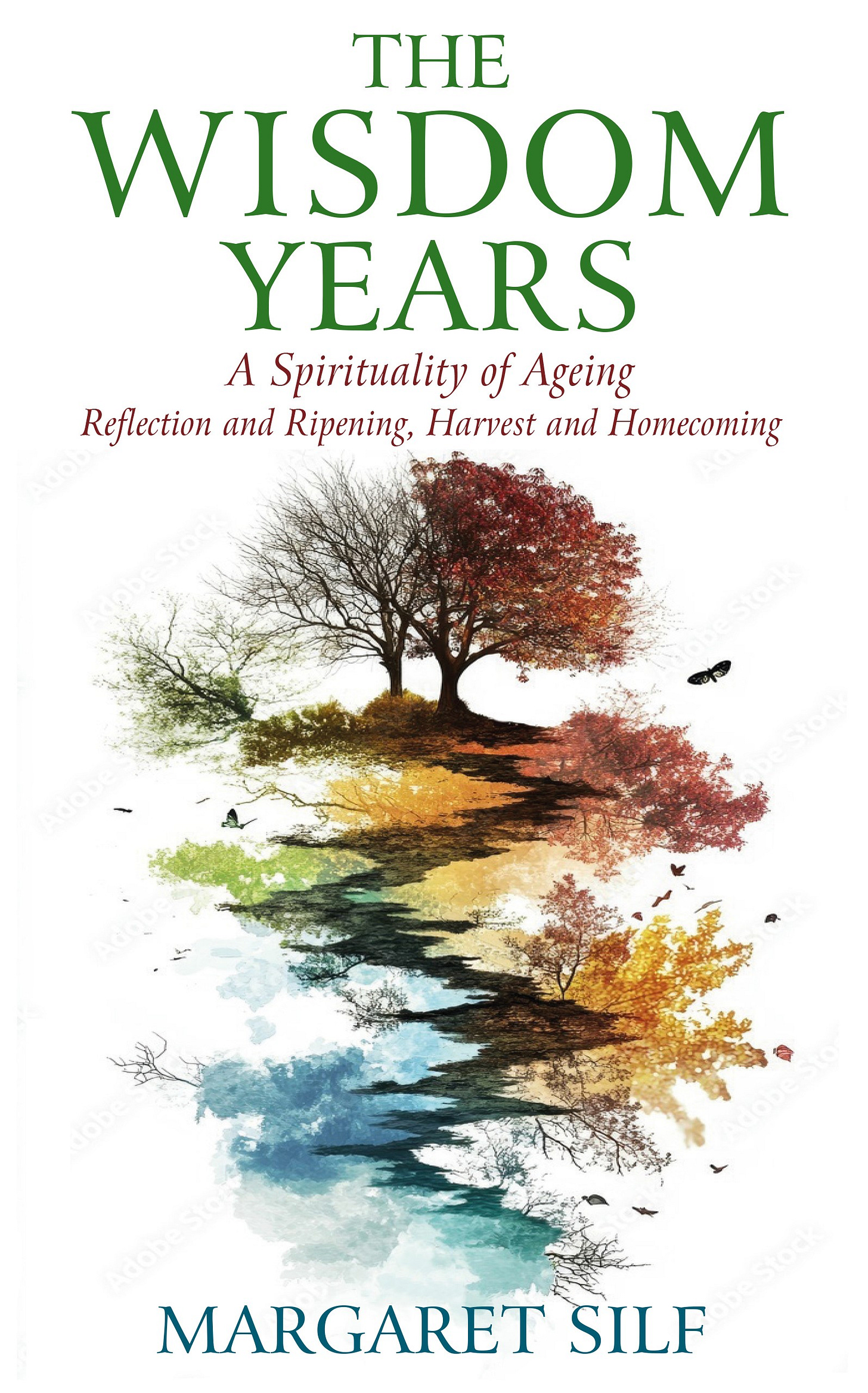

It was this realisation that led me to wonder whether the time had come for me to explore these reflections more fully, and the result is The Wisdom Years: A Spirituality of Ageing, a book due to be published by DLT in September. When I was young we used to celebrate harvest festival, when people brought the best of their year’s labour to the annual ritual of thanksgiving. The harvest table would be laden with cabbages and leeks, flowers and fruits, loaves baked in the form of sheaves of wheat, and these gifts would later be shared out among the wider community.

I like to think of the new book as my own small contribution to the harvest festival of the human spirit, and an invitation to readers to recognise and celebrate their own seasons of ‘harvest home’. My hope is that it might also be a kind of magic mirror, or an unexpected sunbeam breaking through the grey clouds of older age to light up a fresh, perhaps surprising perspective on what it really means to be living and rejoicing in our Wisdom Years.

Margaret Silf is a writer and speaker, committed to working across and beyond the denominational divides.

Her new book, The Wisdom Years: A Spirituality of Ageing, will be published in September 2025. Drawing on the experiences and wisdom learned from many years spent exploring her own spiritual journey, and accompanying others on theirs, Margaret helps you to see afresh the signposts along the path of older age. They are pointers and invitations for us to discover the immense spiritual value of our later years and to recognise, harvest and share the fruits of a life well lived. You can pre-order a copy here.

A number of Margaret’s other books to help you travel the spiritual path, including Landmarks, Wayfaring, The Other Side of Chaos and Hidden Wings, can be ordered from the DLT Writing for You website. Why not choose 3 books for the price of 2? Every purchase made through this website will generate a royalty for the author and for the Inclusive Church network.

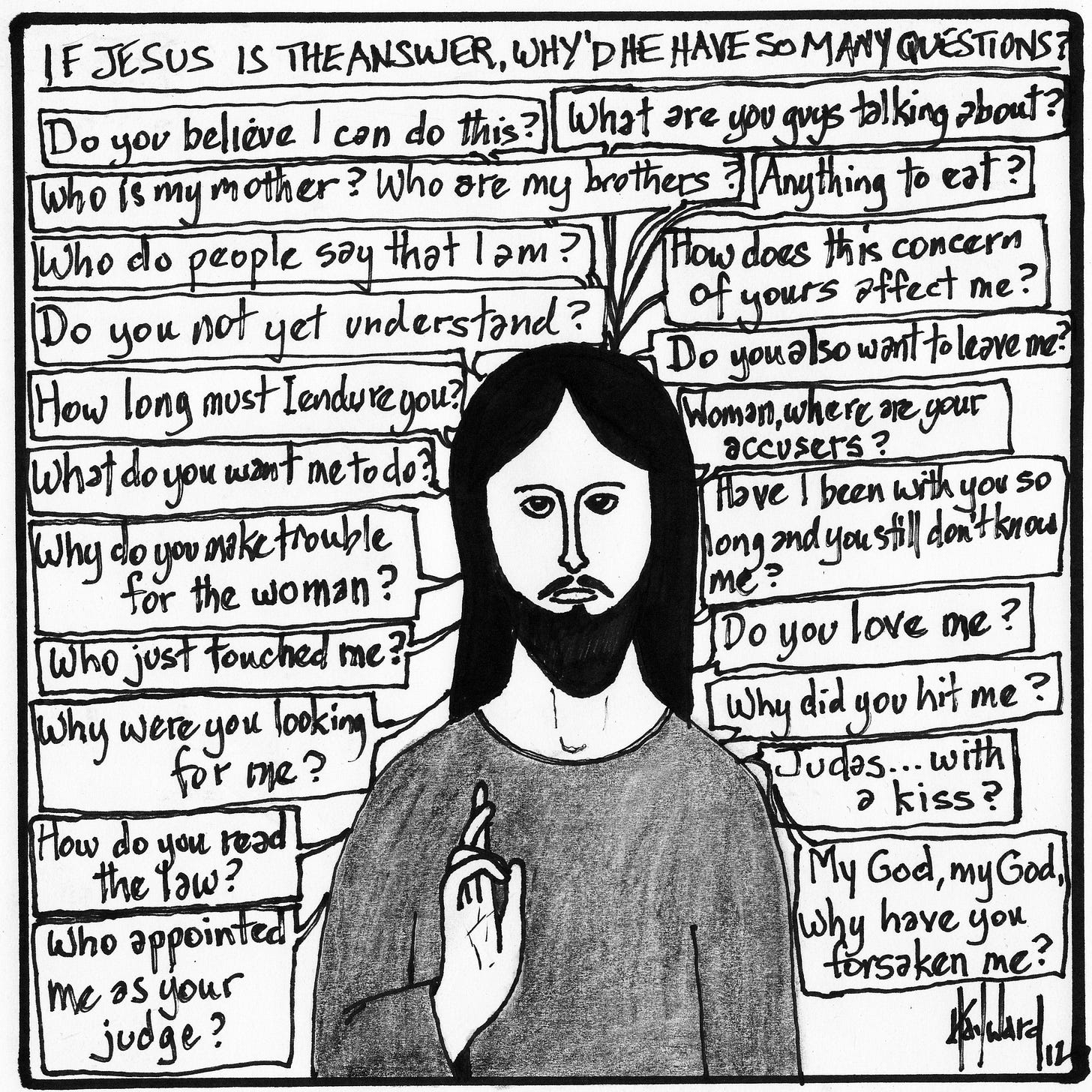

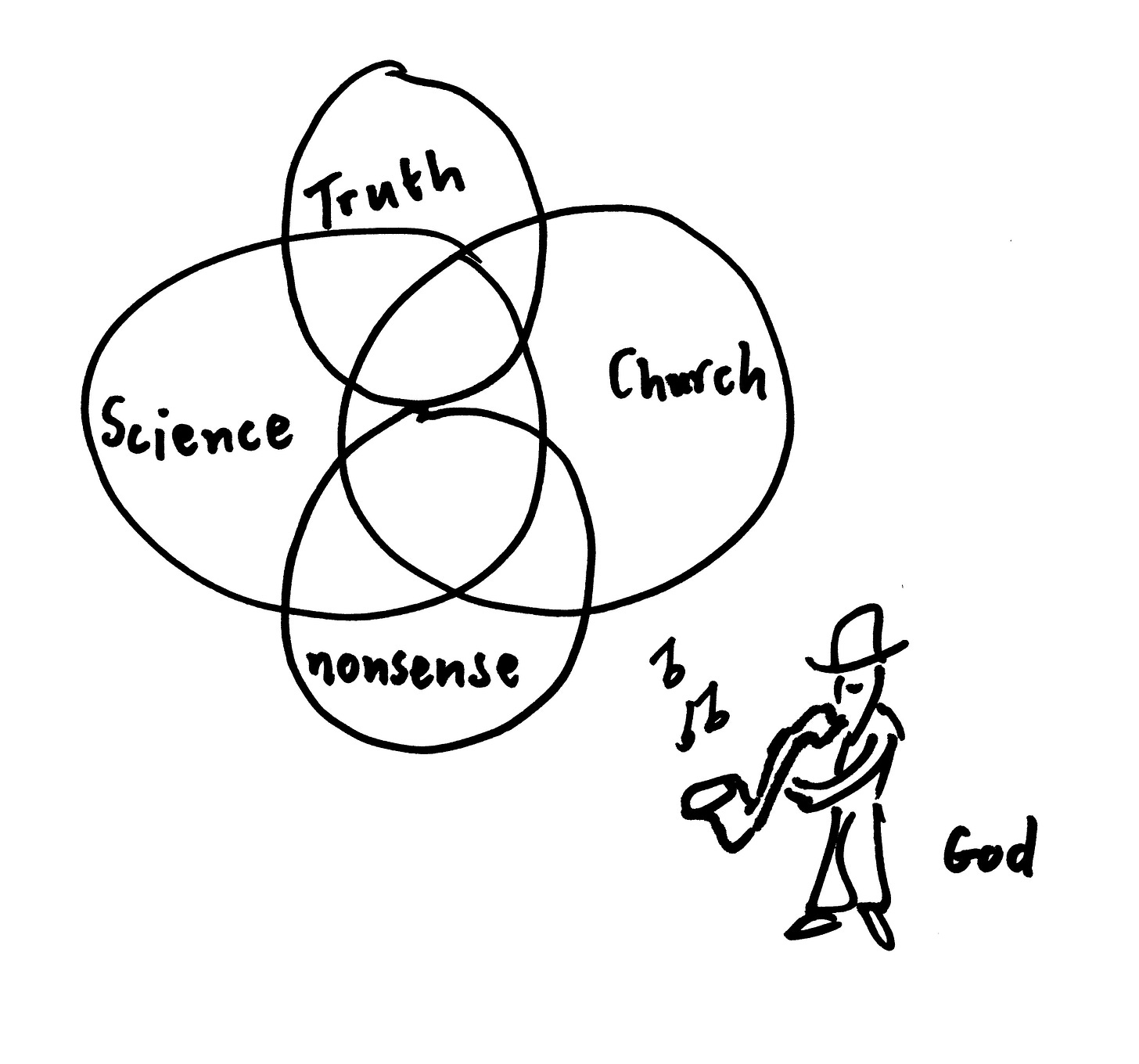

Questions are the Answer

David Hayward

Find many more of David Hayward’s cartoons in Questions are the Answer: nakedpastor and the Search for Understanding.

News from DLT

Darton, Longman and Todd: A Short History 1959-1980. Part One

Douglas Brown, introduced by David Moloney

‘The treasure is within you.’ In God of Surprises, one of DLT’s all-time bestselling books, the author Gerard W. Hughes encourages each of us to examine our own story, suggesting among other exercises that we try writing both our own obituary and our own faith autobiography. Understanding our own story – who we are – is important. Is it possible similarly to examine ourselves as a community or organisation – or a business such as DLT – which is in one sense merely a name under which many different people have worked alongside each other over 66 years, but in another sense something connected, evolved, meaningful in itself?

Much of the story of DLT exists only in the memories of those who have worked for and with the company through particular periods of time. There aren’t too many remaining records of what went on during the 1980s, for example (Helen and I know this, having spent many hours searching through what remains of the company archives one stormy day a couple of years ago at the Norwich Books & Music warehouse where they are stored). But we do have a terrific little history of DLT by a writer named Douglas Brown, commissioned by the company in 1980 – we assume for the company’s twenty-first birthday.

We thought we would reproduce it for you in this newsletter, in three instalments. It's not long, only 12 pages, but it’s a really fascinating document – lively and surprising in places – as a history of our company and a window back in time to the religious and literary landscape of 1959, where it all began. Here is Darton, Longman and Todd: A Short History 1959-1980; part one describes the origins of the Jerusalem Bible.

Darton, Longman and Todd is the story of three men who shared two convictions. One was the belief that the time was ripe for the first-ever Bible in contemporary English. The other was that a lot of people still wanted to read serious works on religion – far more than was popularly supposed in many publishing houses. So vigorously did they hold these views that in 1959 they decided to hive off from Longmans, Green (no less) and form their own company. The publication in 1966 of the Jerusalem Bible turned them almost overnight from a struggling, obscure company to one with an international reputation, a reputation it has constantly enhanced with its rapidly expanding list of some of the most prestigious thinking on religion of our time, thinking indeed usually slightly ahead of the time.

The story of the Jerusalem Bible – a make-or-break venture that came off – is one of the more colourful in the history of publishing. It was the child of confidence and enthusiasm, with a first print-run of copies; it has now sold between two and three million. After unstinted acclaim by church leaders, Bible scholars and theologians of all denominations, it was officially authorized for use by the Roman Catholic Church and, not long after, by the Church of England. It has been much used by the Free Churches as well. It is now universally acknowledged as a force for Christian unity. There was the latest of many examples of this a few months ago when, at the opening by the Queen of Liverpool Anglican Cathedral, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Liverpool, the Most Revd Derek Worlock, presented the Jerusalem Bible to the Dean, the Very Revd Edward Patey. And the Bible is now used regularly on the Cathedral lectern.

The Jerusalem Bible had so much going for it that it was in many ways a publicist's dream, with its unusual history and personalities, the opening up of new frontiers in linguistics, in textual, archaeological and historical criticism, the 'thee's' and 'thou's' and so many other archaisms removed yet at the same time the poetic and the sacral preserved. This last quality is indeed something that has enabled the Jerusalem Bible more than anything to hold its own among the proliferation of new translations and, unlike so many of them, to escape the criticism of reducing style to banality in the search for meaning and accuracy. Yet, paradoxically, some of the JB's most notable achievements in textual accuracy provided the media with some of the most telling quotes, as for instance the use of the divine name 'Yahweh' where most other translations used 'The Lord', and, of course, verse 66 of Psalm 78, 'And he smote his enemies in the hinder parts', becoming 'The Lord woke up to strike his enemies on the rump'. But such is the overall excellence of the text that it has never needed slogans to promote it, and, apart from the occasional newspaper headline, it has never been known either as the Yahweh Bible or the Rump Bible but simply as the JB. Added to all these riches from the product itself, the newspapers, radio and television seized upon the irresistible element of a major achievement by a small private enterprise starting from scratch, uncluttered by an excess of administration but with a staff that always felt itself to be part of a team and shared the confidence and enthusiasm of the directors.

The origins of the Jerusalem Bible itself were modest enough, too. It all began in 1890 with the founding of the École Biblique et Archaeologique Francaise de Jérusalem in disused stables just outside the Old City's Damascus Gate. The founder was Fr Marie Joseph Lagrange, a Dominican who, after studying Assyrian, Egyptian, Arabic and Talmudic Hebrew in Vienna, was sent by his superiors to Jerusalem to start a school of Palestinian biblical studies. After paying for the ground and premises, there was very little money left; it is said that all the equipment the founder had for teaching was a table, a blackboard and a map. The École Biblique, now recognized as one of the leading biblical schools in the world, began in 1946 the task of producing a new French text of the Bible; most notable among the scholars taking part being Père de Vaux of Dead Sea Scroll fame who was nicknamed the 'mountain goat' for his restless and energetic manner. The Dominican archaeologists and scholars not only produced a translation, but also a widely ranging set of introductions, notes and cross-references, making it invaluable not only for scholars but also for the serious general reader.

It was in 1956 that the French La Bible de Jérusalem appeared to world-wide acclaim and the following year work was begun on the English Jerusalem Bible under the late Fr Alexander Jones, an English biblical scholar assisted by a panel of biblical and linguistic experts. It was in no way a translation of the French version, apart from the notes and introductions. Fr Jones devised a special kind of semi-circular stall. He sat in the middle surrounded by the Hebrew, Greek and French texts and the English drafts from the team of experts, comparing one against the other. It was indeed a process of constant revision and counter-revision lasting eight years, and what emerged in the end was a translation in good contemporary English, readily understandable to the modern reader and at the same time providing an accurate translation of the meaning of what the ancient writers were saying. A master stroke was to call in revisers who had both literary qualifications and sound knowledge of the Bible to suggest amendments based purely on style. This undoubtedly led to the Bible's being welcomed as an outstanding example of prose which, though contemporary, was likely to endure – high approval indeed.

It also won world-wide acclaim for the beauty of its typography, with the strikingly clear type and the text printed across the whole page. Chapter and verse divisions were in the inner margin and scriptural references on the outer. Verse endings within paragraphs were indicated by black spots, and poetry was printed throughout in metrical form. And there were section headings and sub-section headings independent of chapters. Michael Longman's love of the meticulous, plus all the time and money the firm could muster in the form of endless sample pages, paid off; another factor in the rapturous welcome. And rapturous it was. The then Archbishop of York, now Lord Coggan and one of the country's leading Bible scholars, described it as 'an outstanding work which will make its mark and long hold a place of honour among translation-commentaries'. Another Anglican scholar, Professor Owen Chadwick, described it as 'this noble bible' and yet another, Dr Eric Mascall, said: ‘The Jerusalem Bible is quite beautiful.’ The Roman Catholic Bishop, now Archbishop, Worlock thought it a work of outstanding scholarship. And there was much more in similar vein from one country after another. Cardinal Heenan said he felt that the editors had contrived to find a language which sounded as fresh to modern ears as the Bible was to the first Christians. He gave a party at Archbishop's House, Westminster, to launch the Bible, with over a hundred leading clerics there including the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Moderator of the Free Church Federal Council, and a Brigadier of the Salvation Army. Members of the firm wore large lapel buttons to identify themselves to the guests. But the occasion was one of such warmth that the stickers on the buttons peeled to reveal to the assembled dignitaries the awesome figure of – Batman!

When the finished copies arrived it was found that the first verse of Genesis had 'siprit' for 'spirit'.

Nor was that the only hazard of the launching. When the finished copies arrived it was found that the first verse of Genesis had 'siprit' for 'spirit'. The Belgian printer had dropped the type on the way to the machine, put it back wrongly and had not check-proofed it. So there was a lot of pulping to be done, although the firm allowed the sale of copies already bound. And one literal crept through and caught the eye of a Sunday Times gossip writer. Psalm 122, verse 4, line 1 read: 'Pay for the peace of Jerusalem.'

In spite of heavy sales from the start, 4 guineas in cloth and £8 in leather meant in 1966 that quite a few found the JB beyond their reach. So the following year DLT brought out a Reader's Edition of the New Testament, cloth-bound, for the incredibly low price of half-a-guinea, but with the introductory matter and notes considerably abridged. This was the first of what might be called the Jerusalem Bible spin-off. The following year saw the Lectionary for Sundays and Holy Days, in 1968 a Reader's Edition of the complete JB at 36s 0d, and, two years later, the Choir Psalter. But perhaps one of the most exciting of all was the publication in 1969 of the Psalms for Reading and Recitation. The poet Alan Neame was given these instructions: 'Re-write the Psalms especially for singing and reading aloud, make sure they are poetical but yet true to the original texts. Use modern idiom but of the kind to influence people to turn to the Psalms again for the sheer beauty of the language. Try to make it a bedside book for Christians and non-Christians alike.' Using his knowledge of Hebrew, he succeeded brilliantly. And in memory of Alexander Jones and his tragically early death DLT published in 1975 the Bible In Order, compiled by Joseph Rhymer: all the writings of the Bible arranged in their chronological order according to the dates at which they are surmized to have been written. Now they have twenty-nine different editions ranging from the complete Standard Edition at £25, bound in leather, to the New Testament (paper) at £1.25. And there are four licensed editions with other firms, chief amongst them the American edition published by Doubleday.

What, then, of the Jerusalem Bible in the years ahead? However distinguished the scholarship and however great the care taken, scholarship itself does not stand still. A complete revision of the whole vast work is now beginning to get under way. By 1971 Darton, Longman and Todd were beginning to see the turnover of the present Jerusalem Bible reach to between a quarter and a third of their total (as it is today) of £600,000 and to reap the income from their English language world rights. Unlike the publishers of many other Bibles they had royalties to pay to the owners of the original French texts, but, on the other hand, in return for that royalty their own reputation had been internationally established and they were able to give to the age not only an outstanding text but more scholarship, more understanding of Scripture than had ever before been combined in a single volume. Not surprisingly, therefore, DLT have begun to direct much of their profits towards this vast undertaking. But the outcome will be a long time in the future and although it will be a very significant event indeed in the history of Darton, Longman and Todd, it will be a Darton, Longman and Todd without the men who gave it their names – a firm that has indeed already moved so far from that day twenty-one years ago when Michael Longman, Tim Darton and John Todd started work in Michael Longman's garden on the outskirts of London, taking with them the contract for the JB from Longman's, who had serious doubts about it, as well as a number of other contracts from a religious list in which Longman's no longer had any interest.

The story – in particular three fascinating pen portraits of Messrs Darton, Longman and Todd – will continue in the next edition of DLT Writing for You.

Remembering Vincent Strudwick

David Moloney

We were very sorry this week to hear this week of the passing of Canon Vincent Strudwick, author of The Naked God: Wrestling for a Grace-ful Humanity, at the age of 92. We worked together on the book in 2016, having been introduced by our mutual friend Judith Longman, and I found Vincent to be all that one could want in a writer: wise, generous, funny, honest and incredibly intelligent. I would have loved to work with him again but a suitable opportunity did not arise, nor for me to know him well enough to write a fitting tribute, so I am grateful to Professor Jane Shaw, Principal of Manchester Harris College, Oxford (and Vincent’s co-author on The Naked God) for notifying me of this article on the website of Kellogg College, Oxford, where he was Emeritus Fellow.

10 Second Sermons

Milton Jones

Milton Jones further dissects the great pastie of faith in 10 Second Sermons: … and even quicker illustrations and Even More Concise 10 Second Sermons.

Puzzles

Not Quite Write

Stephen Poxon

Complete the Bible passage (Jerusalem Bible):

From ____, the perfection of beauty. (Who knew Isleworth was quite so grand?)

Answer below.

Stephen Poxon compiled and edited A Pleasant Year with Father Brown: 365 Daily Readings in the Company of G. K. Chesterton’s Priest Detective.

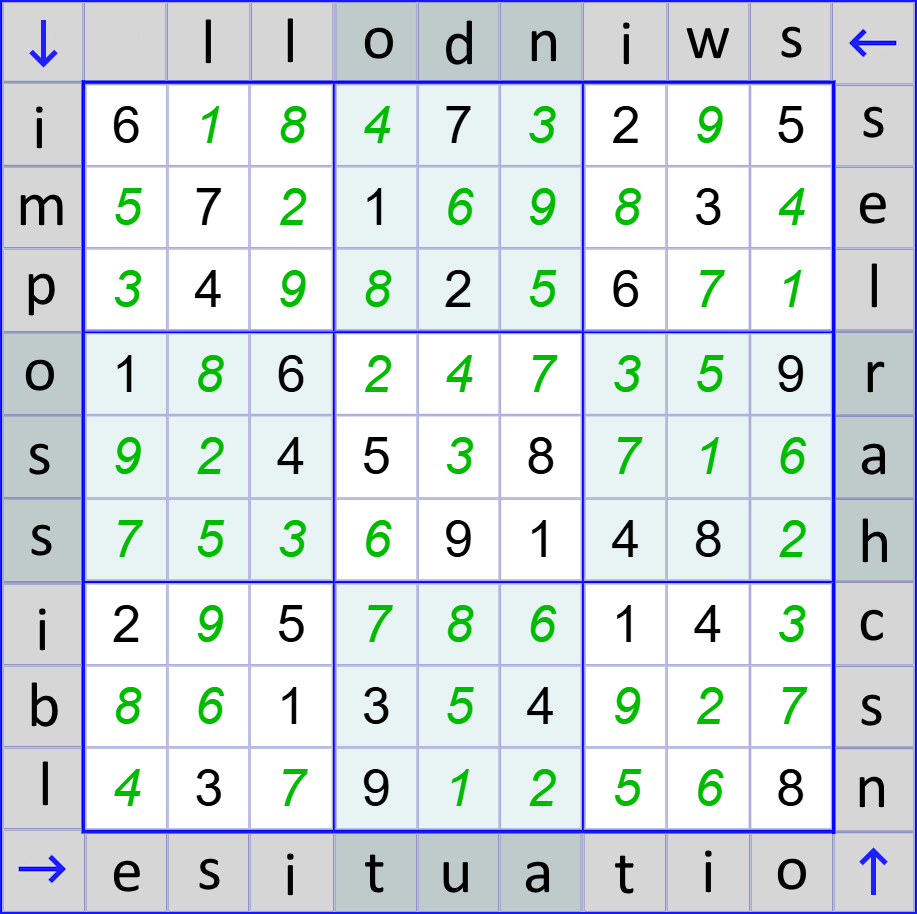

Clerical Errors

Thomas a Quiznas

‘We are all faced with a series of great opportunities brilliantly disguised as ______.’

To find out what, solve the sudoku, then place the letters listed for each number around the edge. (They’re in order; don’t panic!) The answer starts at the top left corner.

1=o, u, l, l

2=i, a, h, i

3=p, s, c, n

4=l, e, e, o

5=m, t, s, s

6=i, i, a, -

7=s, i, s, d

8=b, o, n, l

9=s, t, r,

Answer below.

The fiendish puzzles of Thomas a Quiznas were discovered by Fay Rowland, author of 40 Days with Labyrinths: Spiritual reflections with labyrinths to ‘walk’, colour or decorate.

Theologygrams

Rich Wyld

Discover more of Rich Wyld’s work in Theologygrams: Theology Explained in Diagrams and The World According to Theologygrams: Making Sense of Christianity through Badly-Drawn Diagrams.

Puzzle Answers

Not Quite Write: Zion (Psalm 50:2)

Clerical Errors: … impossible situations. Charles Swindoll